by Barbara J. Wood

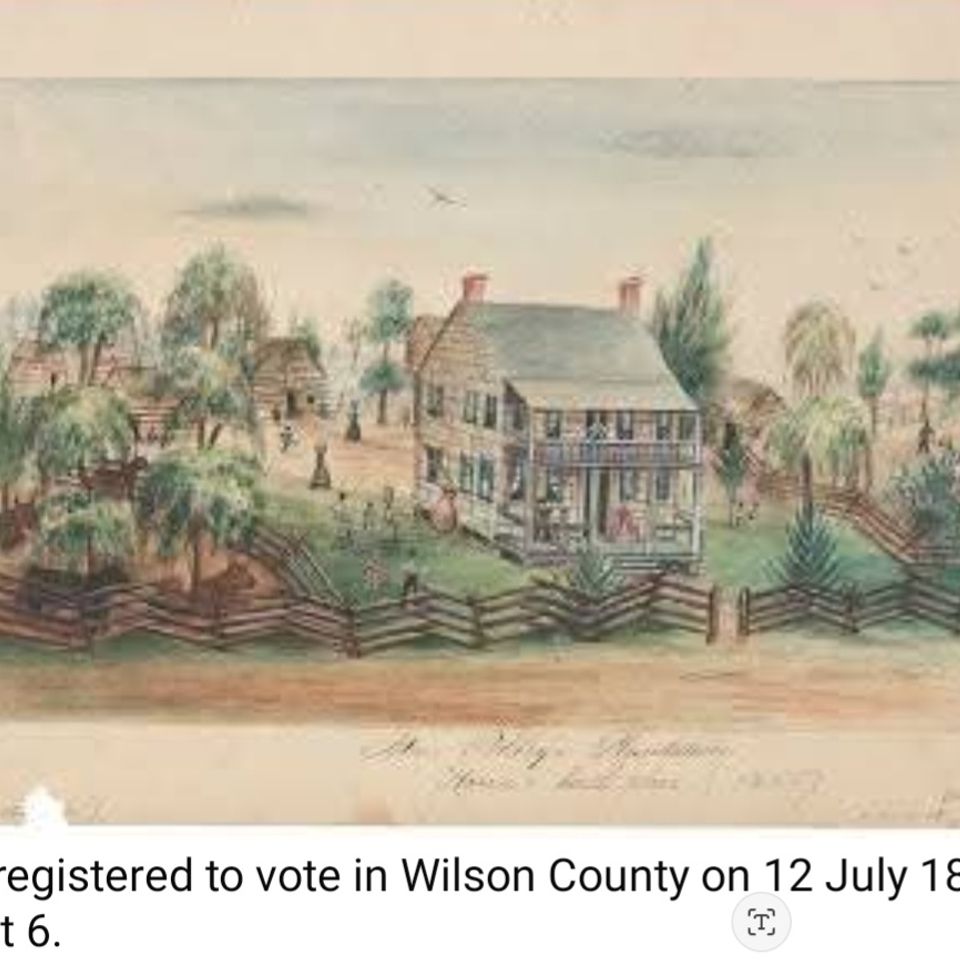

The Enslaved People of the J. H. Polley Plantation, Whitehall, Sutherland Springs, Texas... Jim Bailey.

Jim Bailey (ca. 1822-before 1906)Jim

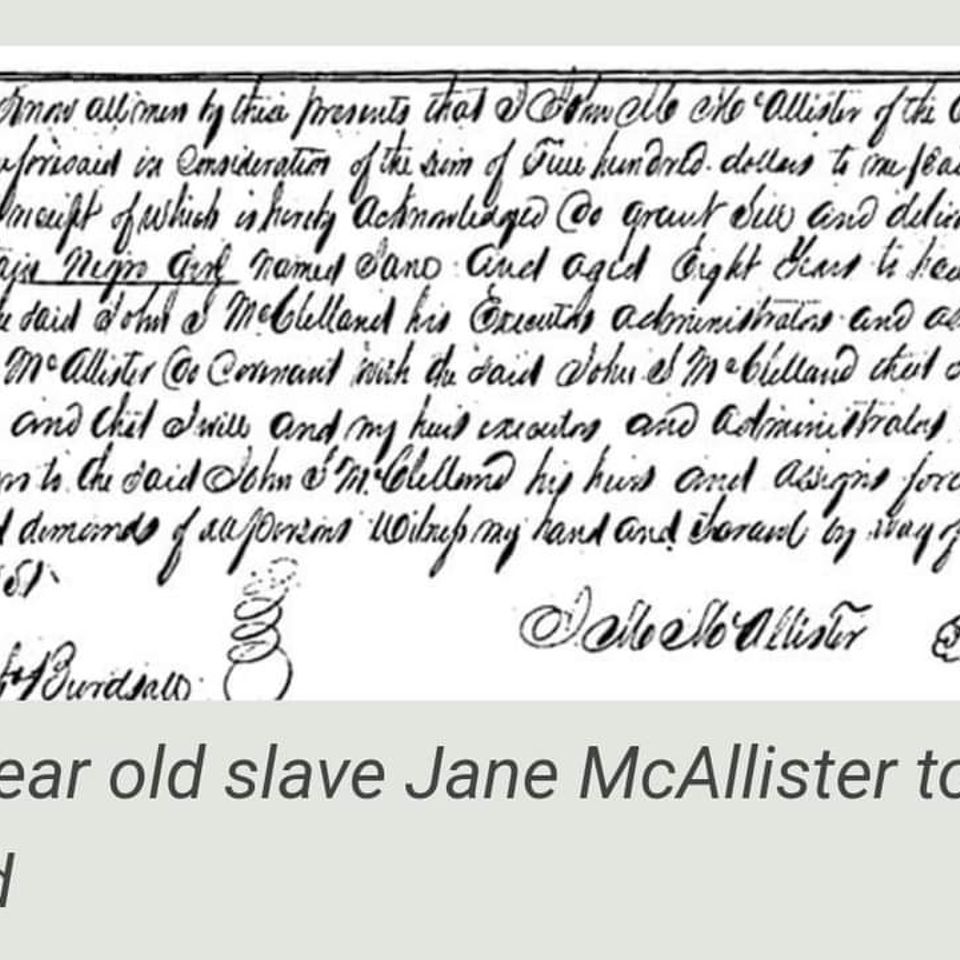

Bailey was born into slavery in the household of James Britton Bailey around 1822 in Brazoria County, Texas. After Britt Bailey's death on 6 December 1832, Jim was inherited by Smith Bailey, Britt's son. Gaines Bailey died that same year. Britt Bailey's last surviving son, Smith Bailey died in 1833 of cholera, with Jim in his possession. J. H. Polley was the executor of their estates, and it is possible that Polley inherited Jim Bailey at that time.

J. B. Polley recorded an episode of Cato and Jim picking mustang grapes to make preserves and being attacked by Indians in his "Historical Reminiscences." Although Golson claims that Jim Bailey did not survive the attack, J. B. Polley tells a different story. In his story, told to him by Jim Bailey as they "sat in front of his cabin, he on the doorstep, and I on the stool he had hospitably insisted on my occupying," Jim survived the Indian attack in 1851, riding away on a horse as fast as he could. In the story Jim is described as "a kind of foreman—in charge of the cattle and horses." Jim is also mentioned in a story from 1858, when he and the other three grown slaves, Rueben, Cato, and Burrell, were hewing logs.

Jim Bailey was among the slaves Polley freed after the news of the Emancipation Proclamation made it to Texas, according to Josephine Golson, J. H. Polley's granddaughter, in Bailey's Light.

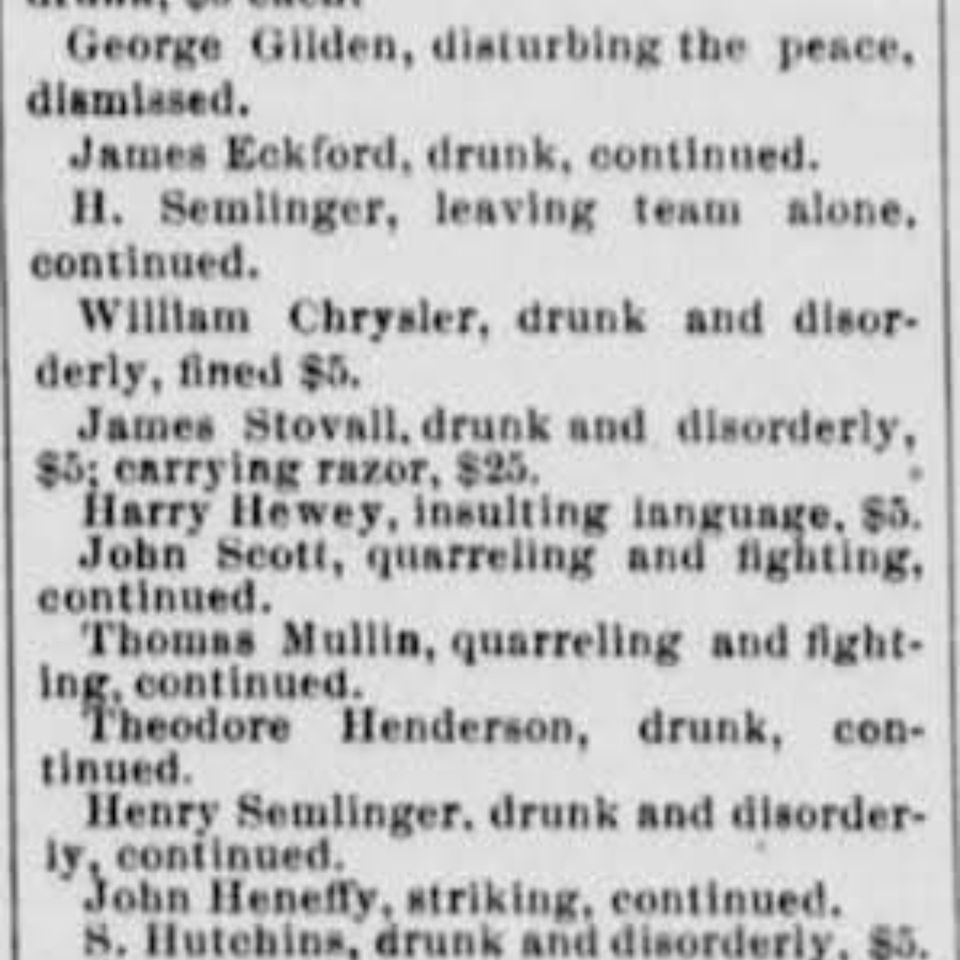

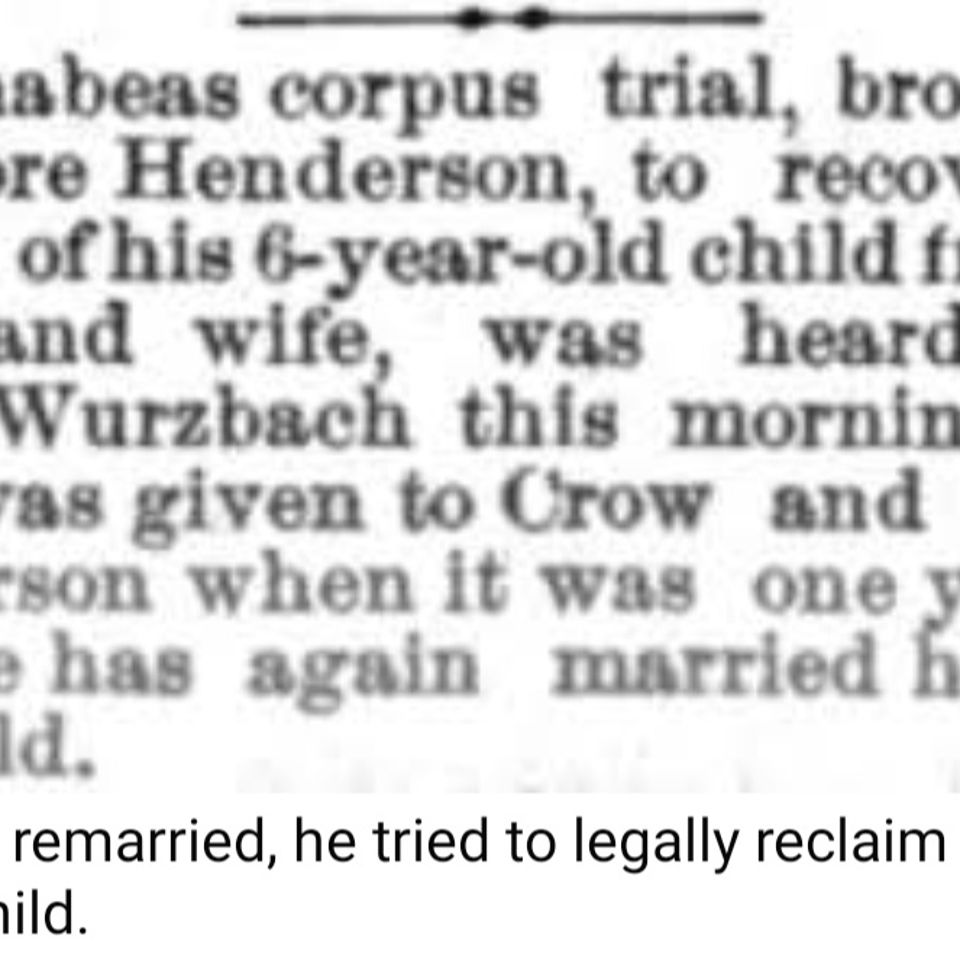

J. H. Polley made a legal agreement with James Bailey, Reuben Robinson, Cato Morgan, Burrell Montgomery, Theodore Henderson, and Albert Nious to employ them as servants until December 1865.

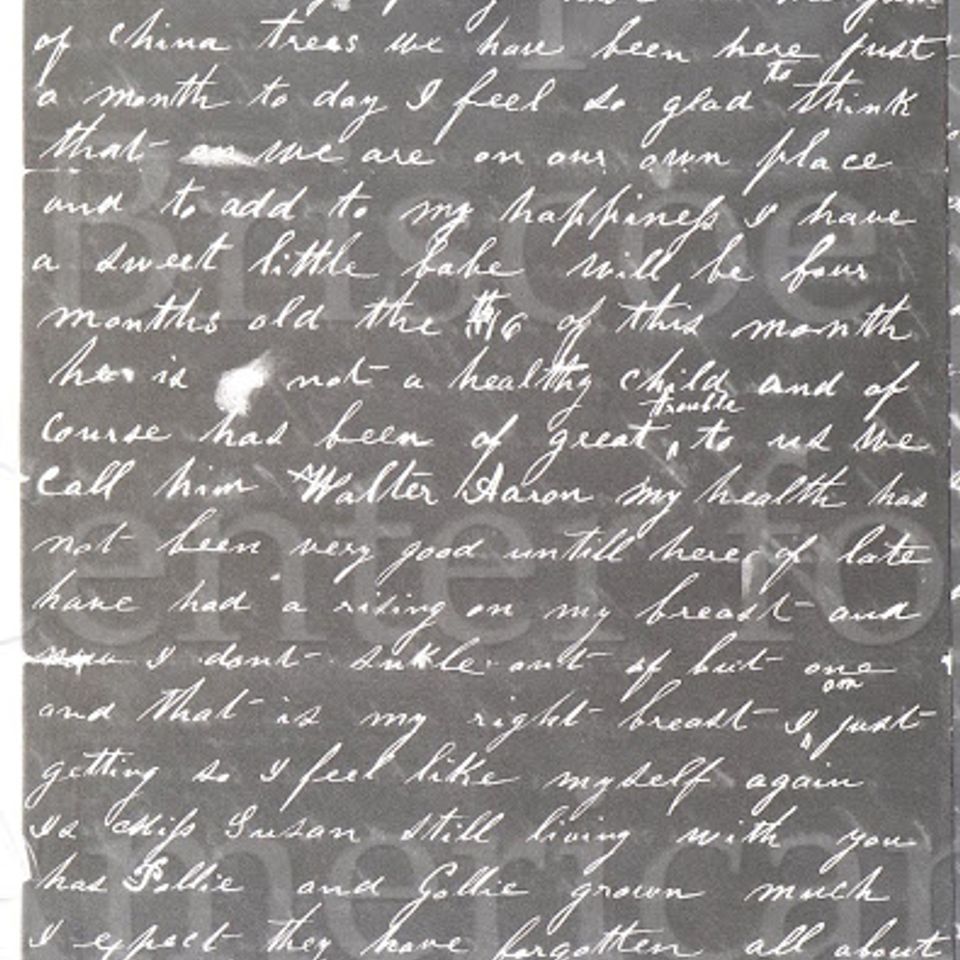

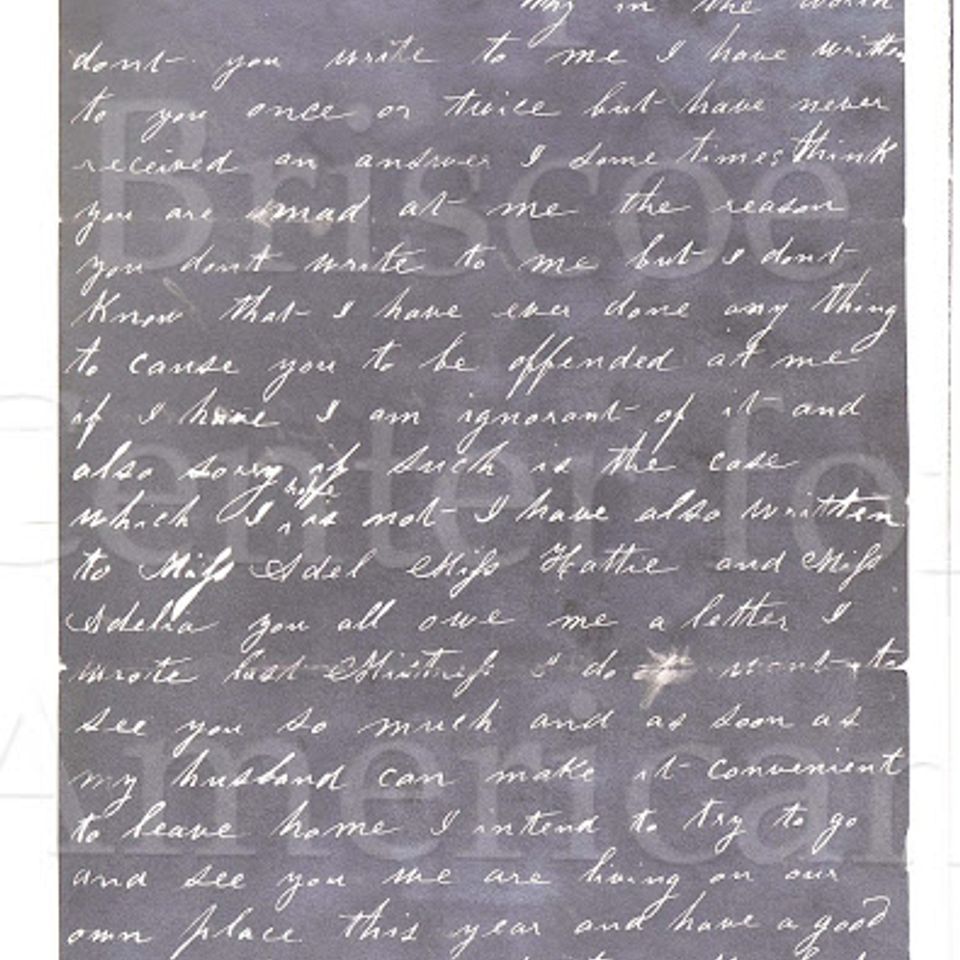

Not finding further mention of Jim Bailey, I am pursuing the idea that Jim gave up the Bailey name and took his family name Nious after he was freed and married Matilda.

His quilt square is "The House that Jack Built."

This biographical selection is from The Enslaved People of J. H. Polley Plantation, Whitehall, Sutherland Springs, Texas 1836-1865. The collection is the work of independent scholar, Dr. Melinda Creech. Dr. Creech compiled and presents a biographical sketch of each of the enslaved along with a unique historic Texas quilt for each individual since photos of the 28 enslaved are not available. The collection is available to view in person at the Sutherland Springs Historical Museum.

***************

Courtesy/ The Polley Association

https://www.polleyassociation.org/enslaved-people-at-polley-mansion

Bailey was born into slavery in the household of James Britton Bailey around 1822 in Brazoria County, Texas. After Britt Bailey's death on 6 December 1832, Jim was inherited by Smith Bailey, Britt's son. Gaines Bailey died that same year. Britt Bailey's last surviving son, Smith Bailey died in 1833 of cholera, with Jim in his possession. J. H. Polley was the executor of their estates, and it is possible that Polley inherited Jim Bailey at that time.

J. B. Polley recorded an episode of Cato and Jim picking mustang grapes to make preserves and being attacked by Indians in his "Historical Reminiscences." Although Golson claims that Jim Bailey did not survive the attack, J. B. Polley tells a different story. In his story, told to him by Jim Bailey as they "sat in front of his cabin, he on the doorstep, and I on the stool he had hospitably insisted on my occupying," Jim survived the Indian attack in 1851, riding away on a horse as fast as he could. In the story Jim is described as "a kind of foreman—in charge of the cattle and horses." Jim is also mentioned in a story from 1858, when he and the other three grown slaves, Rueben, Cato, and Burrell, were hewing logs.

Jim Bailey was among the slaves Polley freed after the news of the Emancipation Proclamation made it to Texas, according to Josephine Golson, J. H. Polley's granddaughter, in Bailey's Light.

J. H. Polley made a legal agreement with James Bailey, Reuben Robinson, Cato Morgan, Burrell Montgomery, Theodore Henderson, and Albert Nious to employ them as servants until December 1865.

Not finding further mention of Jim Bailey, I am pursuing the idea that Jim gave up the Bailey name and took his family name Nious after he was freed and married Matilda.

His quilt square is "The House that Jack Built."

This biographical selection is from The Enslaved People of J. H. Polley Plantation, Whitehall, Sutherland Springs, Texas 1836-1865. The collection is the work of independent scholar, Dr. Melinda Creech. Dr. Creech compiled and presents a biographical sketch of each of the enslaved along with a unique historic Texas quilt for each individual since photos of the 28 enslaved are not available. The collection is available to view in person at the Sutherland Springs Historical Museum.

***************

Courtesy/ The Polley Association

https://www.polleyassociation.org/enslaved-people-at-polley-mansion