by Barbara J. Wood

RANCHO DE LAS CABRAS

WHAT 11 NATIVE TEXAN GROUPS

WHAT 11 NATIVE TEXAN GROUPS .... were at Rancho de las Cabras? Local ranchers had long been aware of the crumbling stone walls that protruded from a tangle of thorny brush at this Wilson County site. Situated on a high point above the San Antonio River, the ruin was a distinctive landmark. And given its proximity to San Antonio, with its rich Spanish Colonial heritage, some thought it might even be another Spanish mission.

After researchers sifted through historic maps and records, however, it became apparent that the site had to be the ranch of Mission San Francisco de la Espada—Rancho de las Cabras, or the Ranch of the Goats. The ranch was built in the 1750s after early San Antonio residents—Canary Islanders—complained that mission cattle were trampling their crops. Espada had large herds—as many as 1,150 head of cattle, 740 sheep, 90 goats, 30 horses and oxen, according to a 1745 report. To meet the resident's demands, the friars arranged for the animals to be moved to mission grazing lands some 30 miles to the southeast, and appointed Indians from the mission to tend to their needs. Apparently, the herders and their families were left largely on their own, as long as the animals were well cared for and the designated allotment of animals was supplied weekly to meet the mission's needs. Removed from the protection of the soldiers at Presidio San Antonio de Bejar, the native workers were vulnerable to attacks by Lipan Apaches and other hostile raiders.

Researchers found little in historic records describing the structures at the ranch complex. The 1772 inventory of Mission Espada made on the eve of its closing, however, described the compound as consisting of four jacals, or structures of upright poles with thatched roofs, one of which was sometimes used as a church or shrine; corrals and pens; and a fenced field for corn. A later account mentions that 26 persons lived at the ranch. This likely included herders and their families.

Ethnohistorian T. N. Campbell, attempting to ascertain which native groups might have been represented at the ranch, found a list of 11 names in Mission Espada records for the period 1753-1767. These included the Assaca, Caclote, Caguamama, Carrizo, Cayan, Gegueriguan, Huarique, Saguiem, Siguipan, Tuqrique, and Uncrauya. Although we likely will never determine which group or groups were represented at the rancho, Campbell believes none of the 11 were native to the area, nor did they speak the Coahuiltecan language. Rather, all of the groups were from extreme south Texas and the Mexican state of Tamaulipas and may have been remnants displaced by Spanish colonies established by Jose de Escandon along the Rio Grande river around 1750.

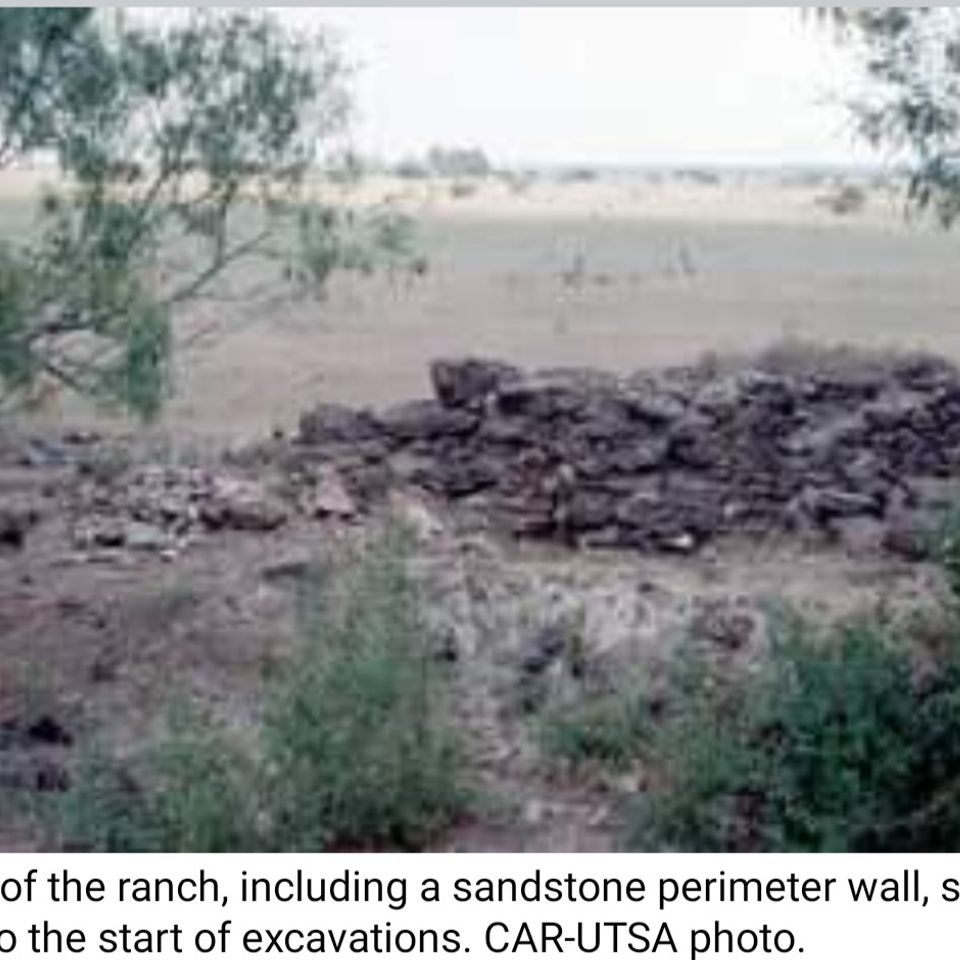

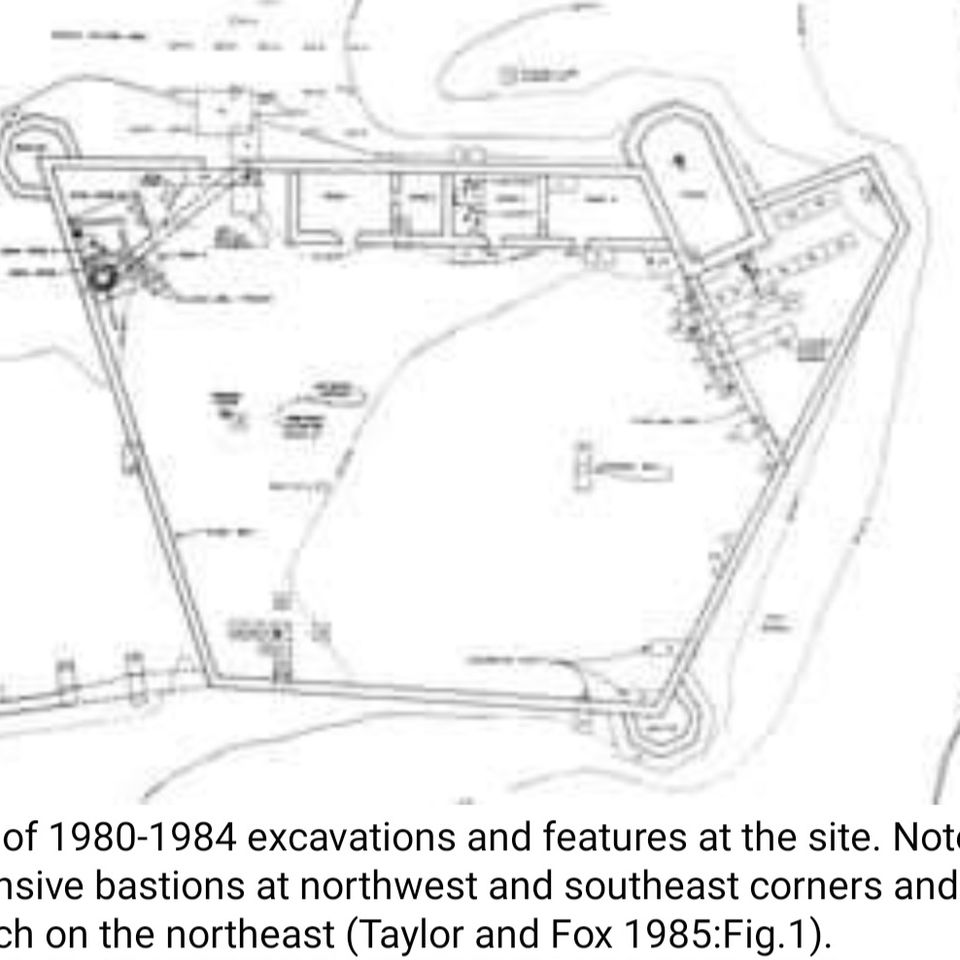

When archeologists visited the site in the 1970s, they found a large standing ruin, enclosed within a perimeter wall of sandstone blocks, remains of several rooms, and bases of defensive towers, or bastions. In 1976, the site and adjacent acreage was acquired by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Archeologists from the Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Texas at San Antonio were contracted to conduct field investigations prior to the historical development of the site for the public. In month-long stints over a period of five years, archeologists from UTSA-CAR mapped the site, tested along interior walls, and probed trash heaps near the two entry ways where gates once were located.

They determined almost immediately, based on differences in stone at different points, that the present outline of the compound is not the original, and that there had been at least two different building phases. Later additions after 1772 apparently included extensions to the wall and completion of a chapel. The hexagon shaped compound was accessed by two gates. Archeologists also found a kiln for making plaster, likely from the chapel interior. Postholes around the south wall were determined to represent jacals, and household items were found on floors.

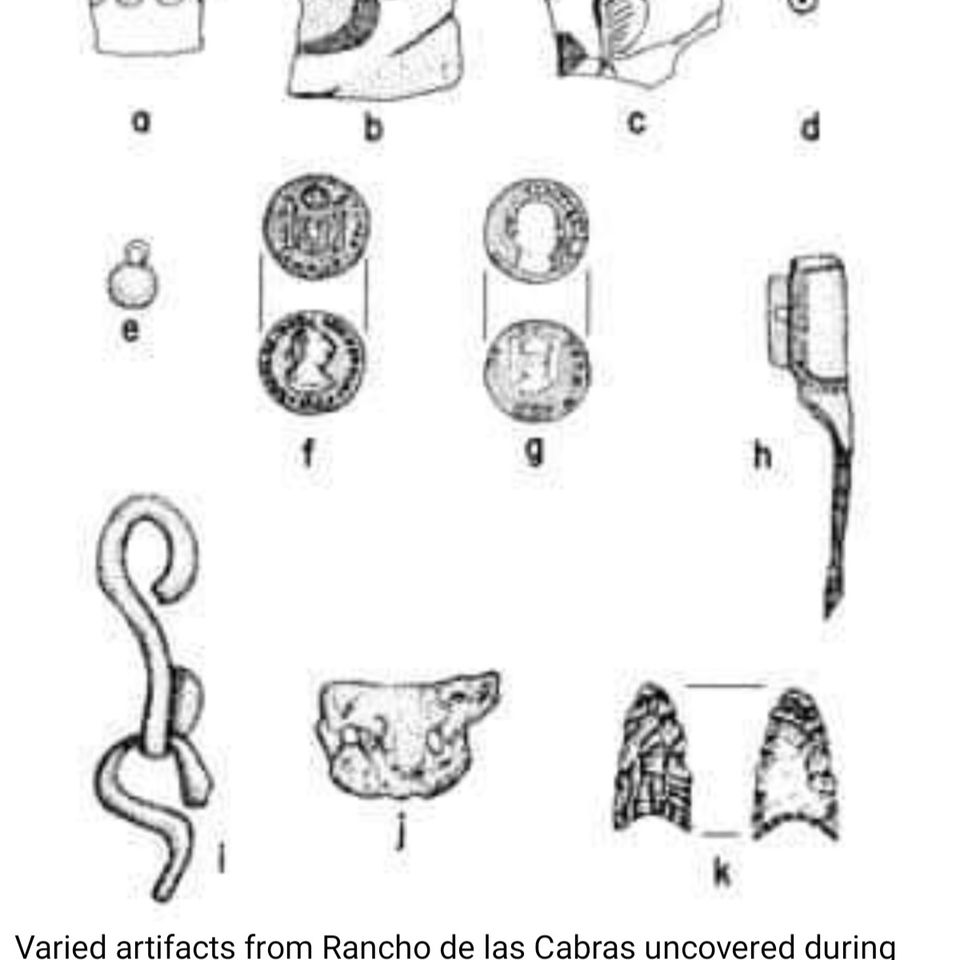

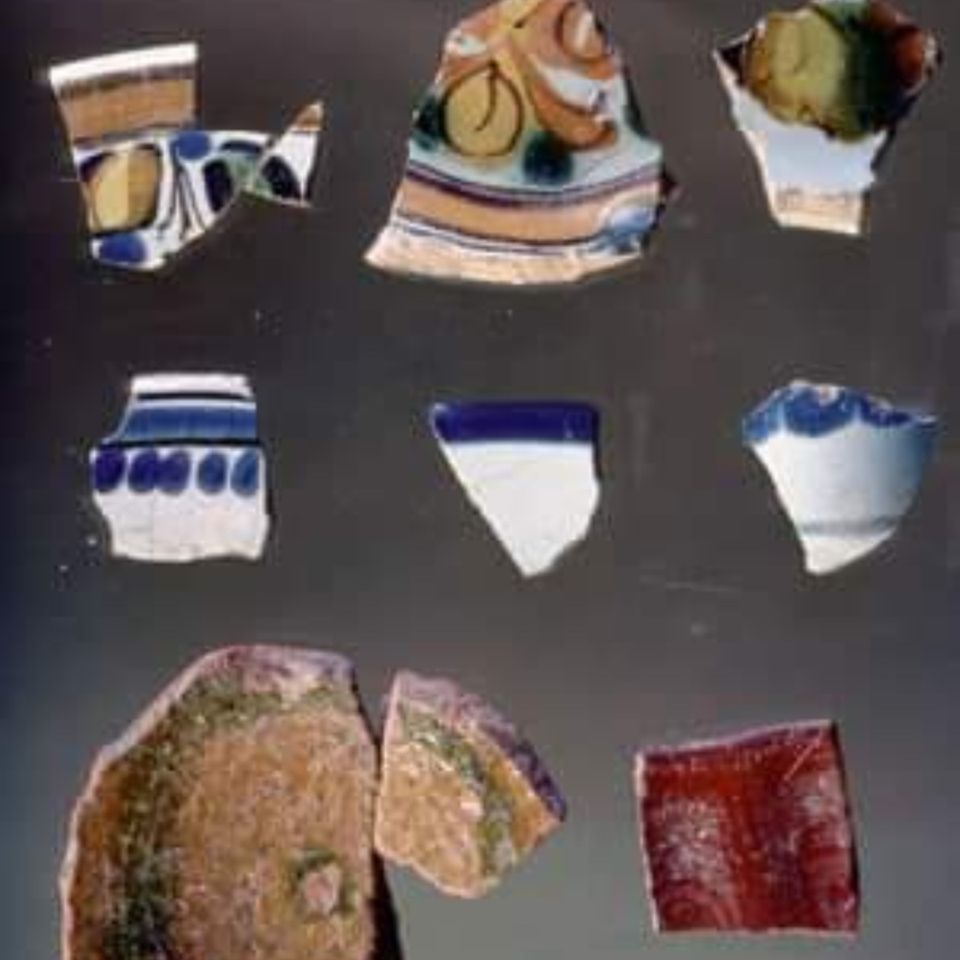

Most artifacts were found in large trash heaps, or middens, located outside the wall. In addition to chipped-stone tools and crude, bone-tempered pottery, which pointed to the persistence of earlier native traditions, archeologists found the remains of imported ceramics, including tin-enameled, Mexican majolicas, oriental porcelain, and French faience; coins; gunparts, and other metal objects; and an array of ornate personal items—fancy metal buckles, jewelry, and crucifixes. They also found chipped-stone gunflints, indicating use of European flintlock guns, and a quantity of bone, indicating a diverse diet of domestic animals augmented by wild resources including turkey, deer, javelina, opossum, squirrel, fish, and turtle.

One of the research interests of the archeologists had been to try to ascertain the degree to which acculturation had taken place among the Indian neophytes, particularly when separated from the mission fold. They found a surprising indication of adherence to mission teachings, given that a chapel was erected, religious items such as rosaries were employed, and European merchandise was used. Although traditional native practices continued, the native vaqueros apparently fulfilled their duties in tending the herds.

As noted by UTSA-CAR archeologist Anne Fox, in a 1989 article on Rancho de las Cabras:

Life at the ranch, away from direct supervision and under extreme stress of threat of Indian attack, might tempt Indians who were a bit shaky in their indoctrination as Spanish citizens to slip back to their earlier habits. The fact that they apparently did not could be an indication that only Indians of long standing and proven loyalty to the mission were chosen for this job since it was so essential to the well-being of the mission residents.

The site has been acquired by the National Park Service and there are plans to include it within the San Antonio Missions National Historic Park Trail.

*******************

COURTESY / texasbeyondhistory.net

Print Sources

Campbell, T. N.

1985 Appendix A. Rancho de las Cabras and the "Cabras" Indians of Southern Texas: Correction of Historical Errors. In Archaeological Survey and Testing at Rancho de las Cabras, 41WN30, Wilson County, Texas, Fifth Season. Archaeological Survey Report 144. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio.

Fox, Anne A.

1989 The Indians at Rancho de las Cabras. In Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands West, edited by David Hurst Thomas, pp. 259-268. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

Ivey, James E. and Anne Fox

1981 Archaeological Survey and Testing at Rancho de las Cabras, 41WN30, Wilson County, Texas. Archaeological Survey Report 104. Center for Archaeological Research , University of Texas at San Antonio.

Sanez de Gumiel, Juan Joseph

1772 Relación del Estado en que se hablan todas y cada una de las misiones, en el ano de 1762. In Documentos Para la Historia Eclesiastica y Civil de la Provincia de Texas o Nueva Philipinas, 1720-1779, edited by Jose Purrua Turanzas, pp. 245-275. Colleción Chimalistic de Libros y Documentos Acerca de la Nueva Espana, vol. 12, Madrid.

Taylor, Anna J. and Anne A. Fox

1985 Archaeological Survey and Testing at Rancho de las Cabras, 41WN30, Wilson County, Texas, Fifth Season. Archaeological Survey Report 144. Center for Archaeological Research , University of Texas at San Antonio.

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park ..... shares that the Rancho de las Cabras was the ranch associated with Mission Espada, but the history of the ranch goes far deeper. In fact, the property was once owned and ranched by one of the first female ranchers in Texas.

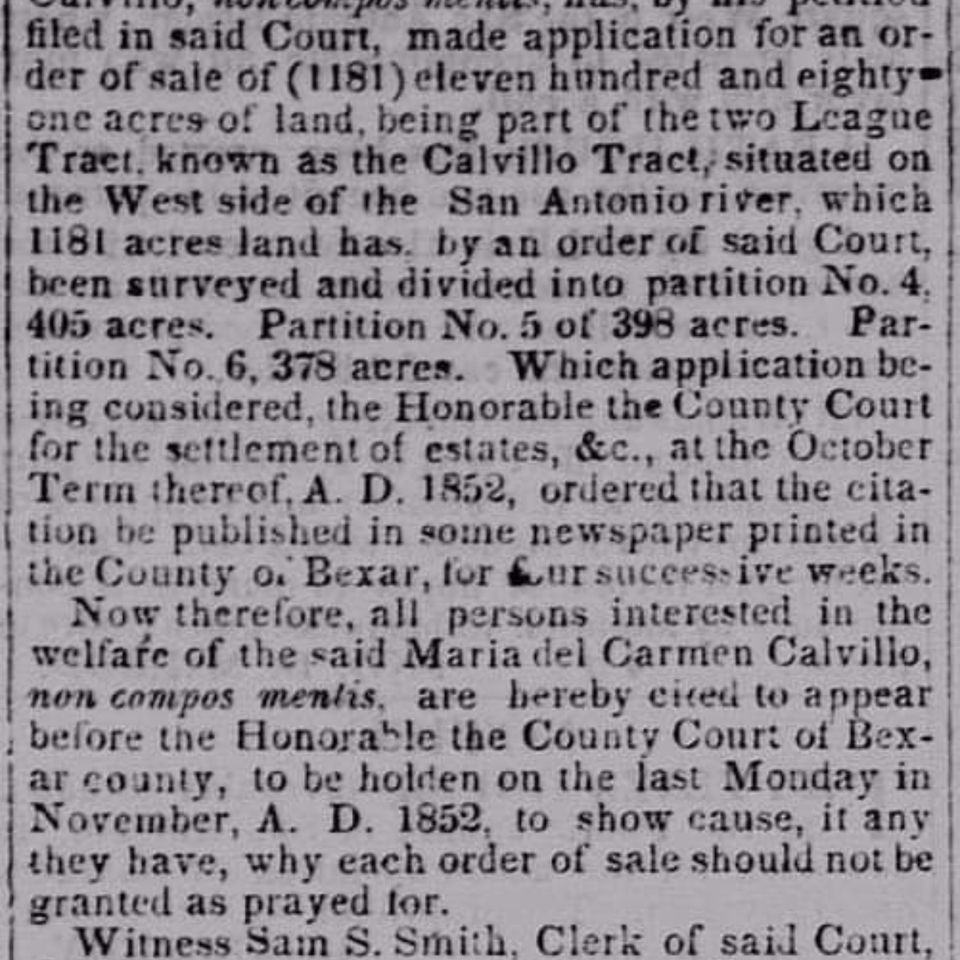

In 1809, the former ranch property passed to Maria del Carmen Calvillo after her father was murdered by a group masquerading as Native Americans that included his own grandson. Maria continued to purchase more property, and by 1830 she was living at the ranch full-time.

Sadly, there is a lot we don't know about Maria. A woman owning and managing so much ranch land would have been unusual for the time, so it is not surprising countless myths and unsubstantiated stories swirl about her.

Maria died on January 15, 1856. Some claim she can still be seen riding the ranch lands, watching over her former property.

******************************

Join San Antonio Missions Historical Parks on the first Saturday of every month (in January it's the second Saturday) for a Ranger guided tour of Rancho de las Cabras to learn more about Maria and the other stories associated with the site!

Reservations are required. To reserve your spot for an upcoming month please email saan_interpretation@nps.gov and include your name, email, phone number and number in your party. Additional details including meeting location to follow with confirmed reservations.

The legend of Mission de Las Cabras

... Back in 1879 one "Pedestrian" and a friend made a trip to the site of an old Mission. His letter follows:

"A few weeks ago, in Company with a friend, I made a visit to the Mission de Las Cabras.

"We thought it would be a pleasant way to spend a Sabbath afternoon. The weather was hot and dry, and a jaunt of eight miles on foot, is certainly getting knowledge under difficulties.

"Three miles below Floresville, we came to a succession of falls in the river, and the contrast from the dried and parched prairie to the cool and pleasant spot on the river was very much appreciated. We could not forgo the pleasure of a little rest in that shady retreat.

"Then we waded the river. The ascent to the Mission was next in order. After much scrambling through brush and undergrowth, we had before us the Mission itself.

"We had no guide; we knew not its history; before us was an immense pile of rocks, which was certainly never made by free labor. The wall must have originally enclosed more than an acre of land. The ravages of time were fast telling on the old ruins. The wall was in some places fifteen or twenty feet high; the roof had all fallen in. There was enough left, however, to make an interesting study.

"The portholes for cannon and guns were in good condition.

"It was a beautiful thought to Christianize and educate the wild savage.

"It was with a sad thought that I left the site of the old Mission, but it certainly repaid me for a visit there.

"The greed of man will not leave the old Mission alone. The ninety thousand dollars said to have been secreted there has been repeatedly looked for after, as there is abundance of evidence to show that the hoe and spade have been in use.

"There is a wild legend told by the Mexicans, and you shall have it as I heard it: When all the elements of nature seem to be at war, and the night is dark and dreary, if you should go alone to the old ruins, you will soon have the pleasure of hearing your teeth chatter. On such an occasion, an old spirit that inhabits the ruins will take its accustomed walk, and, mounting the top of the wall, will wave a light back and forth, as though he were signaling to someone in the distance. However, I did not remain to test the truth of the legend, as I am somewhat addicted to whistling when passing even a graveyard."

"Pedestrian."

We include "Pedestrian's" letter for what it is worth. Someone at the University of Texas advised us she could not remember that such a mission was ever located in this vicinity. Maybe old "Pedestrian" just knew more than we did!

*******************************************************

[This is part of an article or a letter compiled by Alfred E. Menn, which was found in the files of the Wilson County Historical Commission Archives and submitted by Gene Maeckel]

COURTESY / Wilson County News

PHOTOS YELP.com

Dona Ana Maria del Carmen Calvillo

On a June morning in, let's say, 1815, you're riding west toward San Antonio de Bexar along El Camino del Cibolo when a dust cloud signals an approaching rider. As the distance between the two of you closes, you make out a majestic white horse, and, astride the horse, a handsome woman, her long, black hair fluttering like pennants from beneath her wide-brimmed hat.

You recognize the rider as the remarkable Dona Ana Maria del Carmen Calvillo, descendant of early San Antonio settlers, former wife of anti-Spanish rebel Juan Gavino Delgado and, since her father's violent death the year before, flamboyant owner of Rancho de las Cabras along the west bank of the San Antonio River.

Rancho de las Cabras, or Goat Ranch, was established in 1731 by the Franciscan friars of Mision San Francisco de La Espada, known today as Mission Espada, the southernmost of the five missions clustered near the San Antonio River. According to a 1745 report, the mission maintained large herds of cattle, sheep, goats, horses and oxen, but early settlers complained that the animals were trampling their crops. The friars dispatched Native American vaqueros, probably teenagers, to herd the animals 30 miles downriver to the Goat Ranch.

These early-day cowboys lived at the lonely outpost, where they were vulnerable to attacks by Lipan Apaches, Comanches and other raiders. At least once a week, they likely herded sufficient cattle and goats back to town to supply mission residents with beef and cabrito.

According to the Texas Beyond History website, a 1772 inventory of Mission Espada reported that the ranch consisted of four jacals, or structures of upright poles with thatched roofs, one of which was sometimes used as a church or shrine; corrals and pens; and a fenced field for corn. A later account mentioned that the ranch was home to 26 people, including herders and perhaps their families.

"It's the only known extant mission ranch that still has standing architecture," National Park Service archaeologist Susan Snow told me.

The mission operated the ranch until secularization in 1794, when the Spanish government sold church properties to private owners. The rancho's new owner was Ygnacio Francisco Xavier Calvillo, an early San Antonio settler. When he was killed by bandits in 1814, his daughter took over the ranch.

By all accounts Ana Maria del Carmen Calvillo was a remarkable woman. Born in San Antonio in 1765 to Calvillo and his wife Antonia de Arocha, a descendant of Canary Islanders, she was the eldest of six children. She married Juan Gavino de la Trinidad Delgado around 1781. The couple had two sons, both of whom died young, and three other adopted children.

Between 1811 and 1814, Gavino was part of an active and often bloody rebellion around San Antonio against the Spanish crown. Maria apparently left her husband during this period, perhaps to protect the family's land holdings, and let it be known that he was dead. He wasn't.

"She could be something of a scoundrel," said Tambria Reid, a Floresville High School art teacher and knowledgeable local historian. "For several years, Dona Ana Maria del Carmen Calvillo was my research passion."

On April 15, 1814, her father, Ygnacio Calvillo, was murdered during a raid initially thought to have been perpetrated by Indians. A later investigation revealed that the attackers included Calvillo's own grandson, disguised as an Indian.

With both father and husband no longer in the picture, Ana María Calvillo gained control of Rancho de las Cabras. Unlike their American counterparts, women in Spain and in Spanish Texas had the right to hold property under their own names and could sell any property they had owned before marrying. Property purchased or inherited during the marriage belonged to both spouses.

On Aug. 28, 1828, Ana Maria Calvillo formally petitioned the Mexican government for a new title to the ranch. It was granted the next month.

In the coming years she increased her livestock operation to perhaps 2,000 head of cattle, added an irrigation system and a mill and expanded her crop production. She also managed to get along with nomadic indigenous tribes by offering them cattle and a camping site when they passed through the area. She died in 1856 at age 91 and bequeathed the ranch to two of her adopted children.

Archaeologist Snow said that artifacts suggest that the ranch "changed in use through time," perhaps evolving into a central gathering place for the area or an informal inn for travelers.

In 1976, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department acquired

99 acres from private owners, including what remained of the old ranch structures. Without funds to preserve the crumbling rock walls of the compound, Parks and Wildlife buried the ruins in sand to prevent further erosion and vandalism. In 1995, the National Park Service acquired the property, now part of the World Heritage Site of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park.

NPS biologist Greg Mitchell oversees the site, just off Highway 97, five miles south of Floresville. The dirt road to the ranch is unmarked at the highway and is normally closed to visitors, although UT-San Antonio and NPS archaeologists have excavated the site. Area Girl Scouts and the Junior Historians Club from Floresville High School, under Read's sponsorship, have helped clear trails.

Maybe by the fall, Mitchell said, the site will be open to the public, perhaps two weekends a month. He'd love to find additional volunteers to help him maintain it.

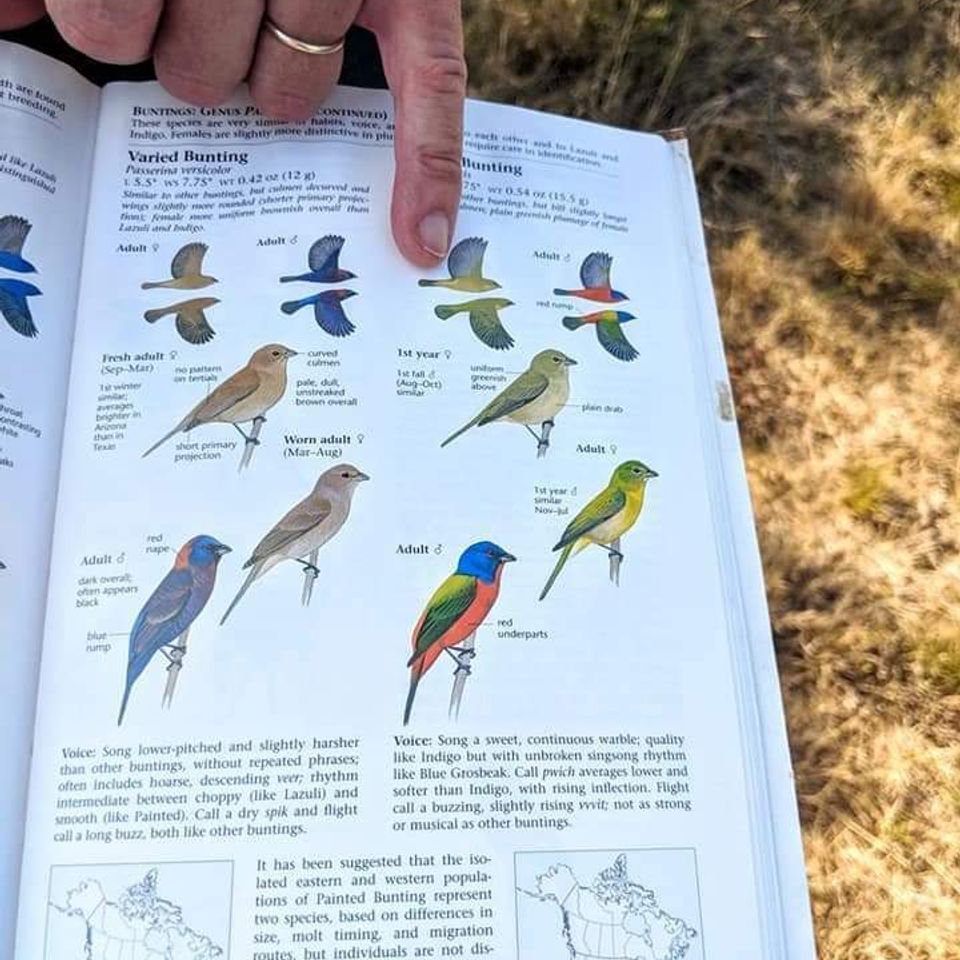

On a hot, steamy morning last week, we ambled along a quarter-mile hiking trail through rangeland Mitchell hopes will revert to native prairie. Jumbled sandstone rocks, once part of ranch fortifications, jutted up through their protective covering of sand and grass. We walked past a depression in the ground that would have been a stone quarry and descended a steep ravine into lush, thickly forested San Antonio River bottomlands. Mitchell said alligators have been known to lurk in a nearby oxbow.

I told Mitchell I had read that Ana Maria's ghost — astride a white horse, her long hair flying — had appeared off and on through the years. Since the Michigan native is often alone at the site, I wondered if he had seen her. He said he had not.

Knowing her, of course, is more important than seeing her. As Read has written, "Doña Anna María del Carmen Calvillo was a strong, courageous and spirited Spanish/Texas woman, experienced in riding horseback, handling guns, managing her ranch, getting along with others, and a proud steward of her land."

This almost-forgotten woman, an integral part of the state's ranching heritage, deserves to ride her white horse into the history books. (Written by Author Joe Holley, Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize)

************

COURTESY/ Joe Holley