by Barbara J. Wood

MILITARY

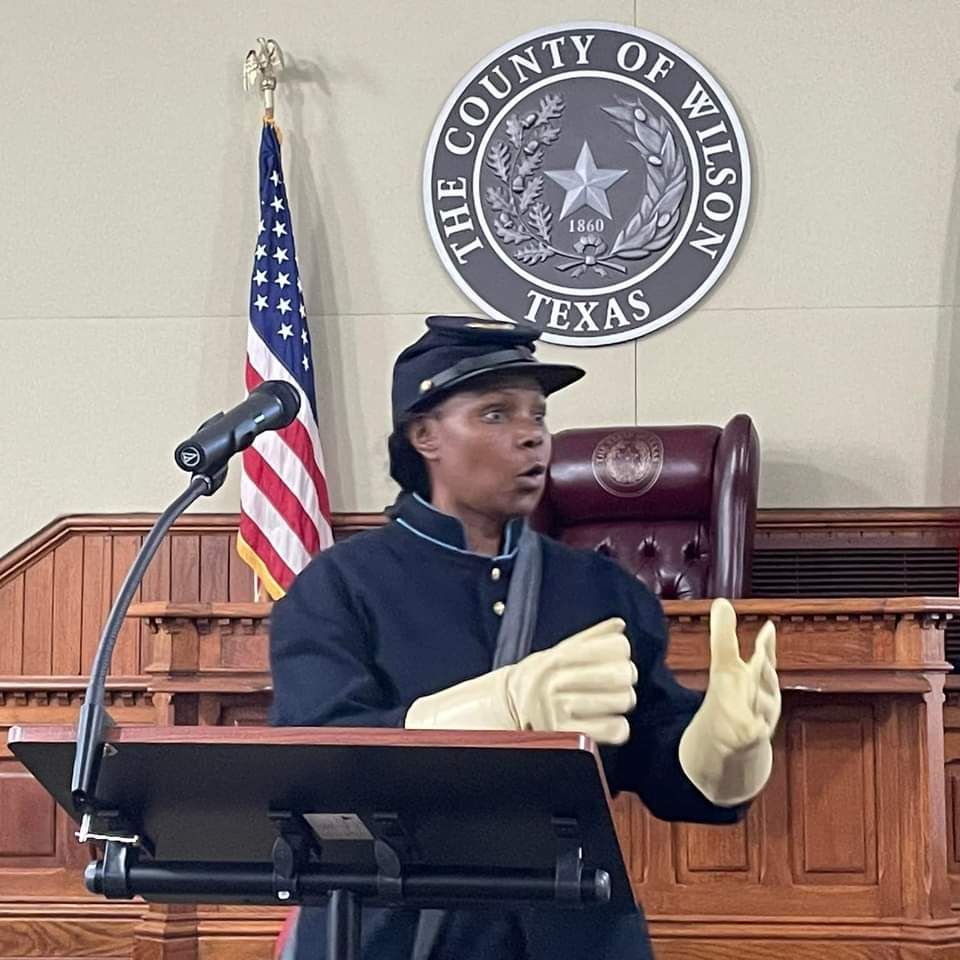

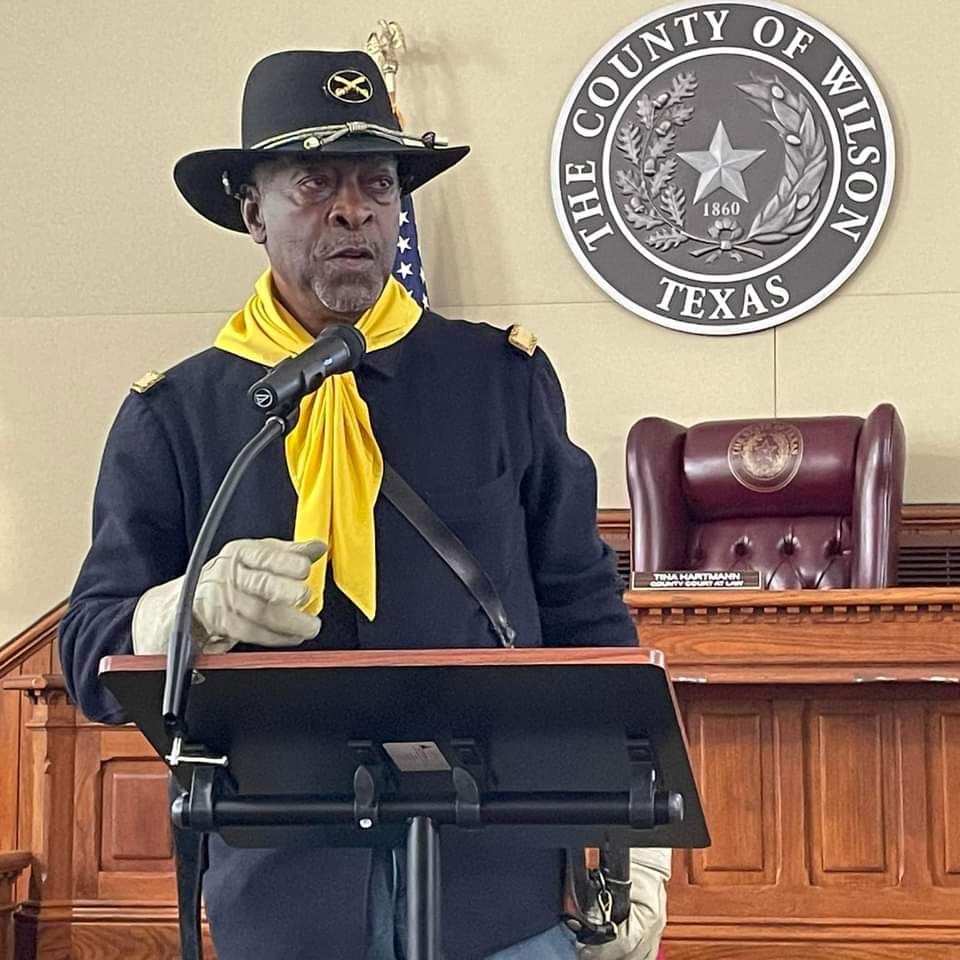

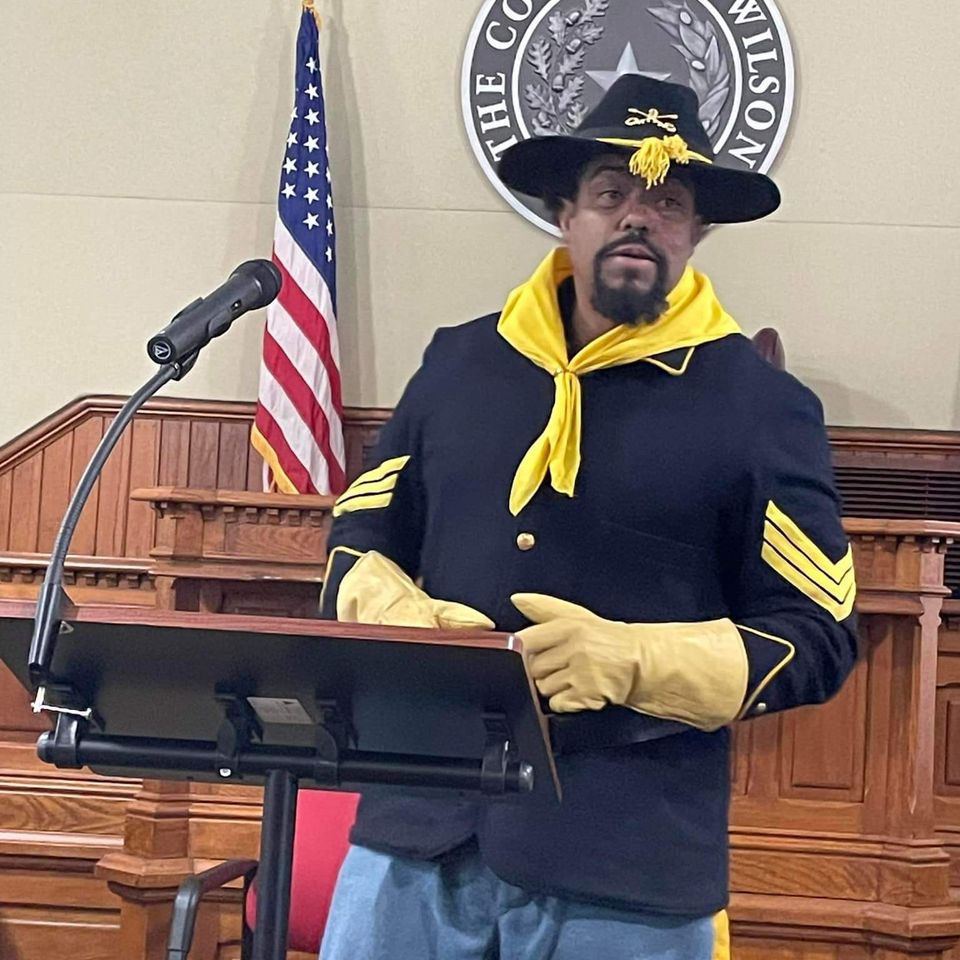

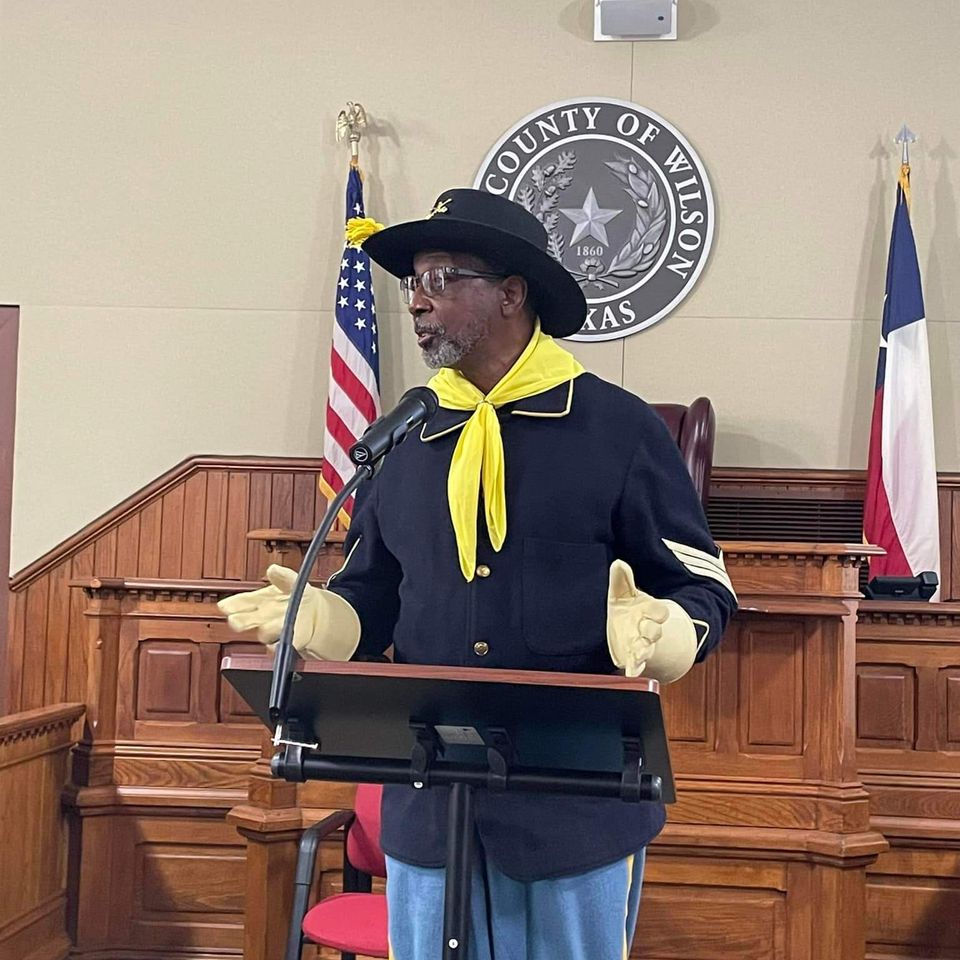

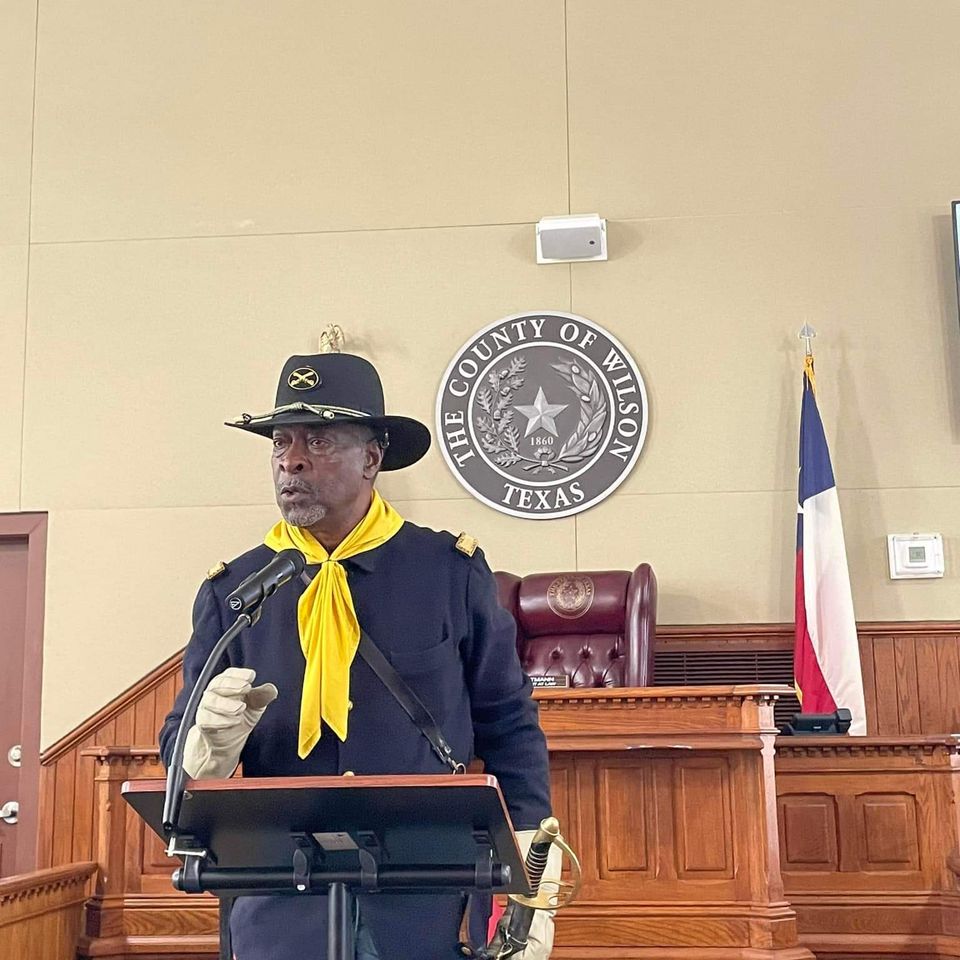

Bexar County Buffalo Soldiers

Wilson County Historical Society shares, "We had an excellent meeting tonight and were blessed with a presentation by the Bexar County Buffalo Soldiers. We learned much about the Buffalo Soldiers history and about each of the personas—the first black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, the only documented woman to serve as a Buffalo Soldier and three Medal of Honor recipients.

Captured: Prisoner of War

Wilson County News, 2002

By Mary Drennon

FLORESVILLE — Area residents mostly likely have seen Gene Matthews around town. He's everywhere.

By Mary Drennon

FLORESVILLE — Area residents mostly likely have seen Gene Matthews around town. He's everywhere.

His favorite spot is Olivia's Mexican Restaurant, where you can find the unassuming, friendly man nearly every day.

To talk to him, you would never know he has such a colorful history. Not unless you ask him.

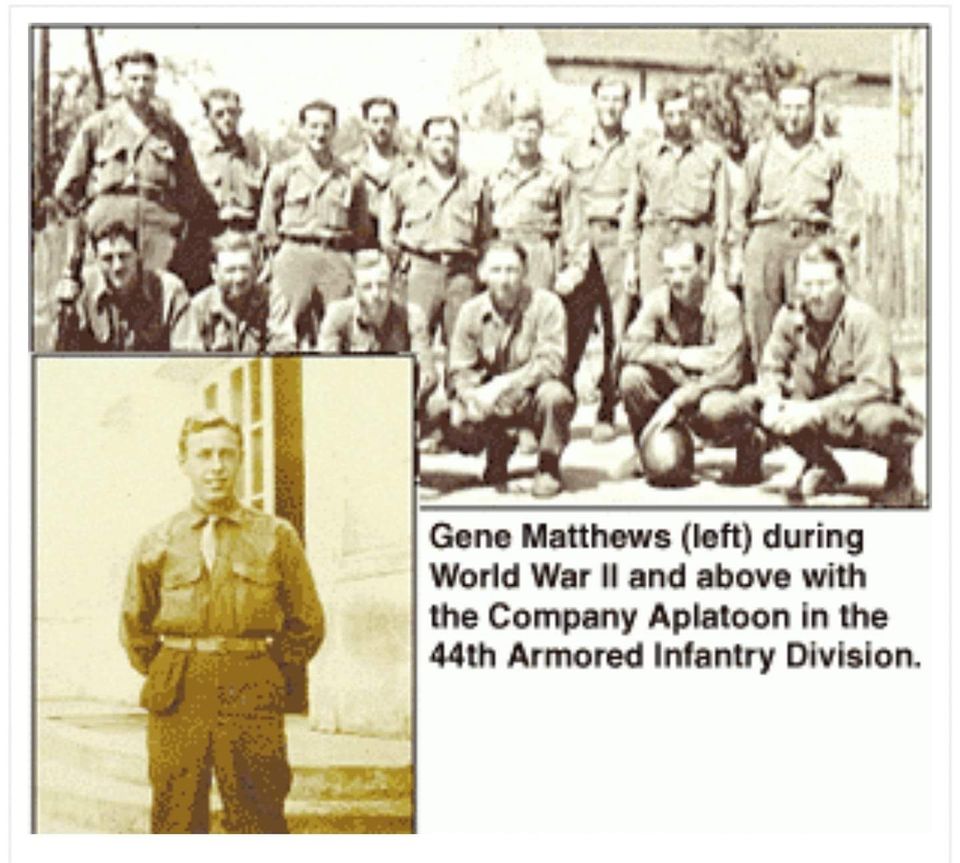

A one-time soldier in the 6th Armored Division — nicknamed the "Super 6" — Matthews has been shot at, laid up for weeks in a hospital, fought in the Battle of the Bulge, and served a brief stint as a prisoner of war.

He served in two different Army outfits, shot down enemy planes, and wandered the countryside of Bastogne, Belgium, running from the Germans.

None of his adventures, of course, were planned.

He received the usual "greetings" in Homestead, Fla., from President Roosevelt in 1941, when he was drafted at the tender age of 18. It was off to basic training for World War II.

After 14 weeks of infantry training in Little Rock, Ark., he was sent for an additional 12 weeks of combat-engineering training at Camp McKain, Miss.

For his first round of duty, he was sent to England with the Combat Engineers, where he traveled with the troops over the English Channel and landed at Omaha Beach. It was there he saw his first action, building "Bailey" bridges over water barriers to get equipment to soldiers already fighting on the other side.

The bridges were built in sections, with wooden panel floors attached to sides made of steel. The entire bridge was built one section at a time. When three or four panels were fashioned, the bridge was placed on rollers and pushed out over the water.

His job, Matthews said, was to keep the wooden planks bolted to the bridge when it came under fire and was damaged. He and a partner would scramble out, relying on others to fend off enemy fire while they made repairs.

In one incident, with the enemy furiously attempting to keep the troops from building a bridge, Matthews had a close call.

He was out over the water, repairing a bridge with a fellow soldier. In a rain of shellfire, one knocked out the back of the bridge, causing the whole structure to fall into the water. Both men fell with it, but were unharmed.

With the enemy firing away, he and his friend swam underwater to get back to their side and safety, Matthews said. To top it off, they still had to go back and repair the bridge.

"It was scary," he said. "If anybody tells you they weren't scared, they are lying."

That assignment lasted for about three months.

For his next assignment he wound up in the 44th Armored Infantry Battalion, in the "Super 6" Armored Division, which at times served in Gen. George Patton's 3rd Army.

Matthews rode a half-track — an armored vehicle with a flexible, mounted 50-caliber machine gun that rotated 360 degrees for optimal firing power — serving as the No. 2 gunner with the 81 mm mortar platoon (Company A), right in the middle of the action.

Sometimes "dog fights" — German planes fighting American planes — would take place right on top of them, Matthews recalled.

His squad shot down a few of the planes, he said, and got shot at in return. He even saw some pilots fall out of their planes without a parachute when the plane rolled upside down. It was a disturbing site, he said.

"I don't know what hell is like, but I got a good idea," said Matthews.

In the Battle of the Bulge, Germans surrounded Matthews' unit for two solid weeks. It was a frightening experience. Often, the soldiers slept in foxholes, waking up to ice covering their bedrolls.

"You prayed to the man upstairs a lot," said Matthews.

It was after this major battle when German soldiers, somewhere outside Bastogne, captured Matthews and three of his fellow squad members.

The squad had been sent on foot to scout the immediate area and ran into some German soldiers lingering in the night, hoping to make a few last-minute captures. He and the others were caught and taken to a holding camp where other American prisoners awaited transport to the regular prison camps.

The four men looked for a way to escape.

The camp was located in an open field, so tower guards could see if anyone tried to escape. Because it was out in the open, the men were allowed to walk the yard and were left pretty much to themselves, Matthews said. From the first night, under cover of darkness, they dug in the dirt, packing it lightly back down each time so no one would discover it.

For nine days they dug. Then, one night, they scooted out under the fence and took off running across the open field. Before they had made it to a wooded area about 75 yards away, the lights came on, and Germans started shooting at them, Matthews said.

The men ran even faster. And then, they heard the dogs. Fearing a quick capture, they headed for a stream — relying on Matthews for direction — and went tramping down into it in an attempt to throw off the dogs. It worked, and the sound of the dogs became fainter, Matthews recalled.

The men relied on German farmers who were not sympathetic to the German cause, thanks, in part, to a squad member's ability to speak fluent German.

For six days they ate mostly raw eggs and potatoes, wandering from farm to farm in an attempt to find American troops.

Finally, they found an American outfit, who informed them the 6th Armored Division was only six miles away. They walked the rest of the way, and caught up with the 44th Battalion.

Since the men had not been locked up for the allotted time that allowed prisoners of war to return home, they were sent right back into action.

All in all, Matthews received a Bronze Star for helping get injured men in his outfit out of harm's way, and the Purple Heart for a stomach injury from an unexploded shell that slammed into him.

After all the fighting and dangerous conditions, it was frostbite and jaundice that nearly brought him down. In fact, he spent 18 weeks in a hospital in Nancy, France, while the rest of the troops went home together.

He was honorably discharged on Dec. 7, 1945.

Matthews never really climbed the Army's ladder of success, as he was too much of a "mouth" in the service, constantly losing his stripes, he laughed.

It is through sharing stories such as this with our readers that we have a chance to say "thank you" to men like Matthews for the remarkable service they have rendered.

Think of Matthews, and others like him, on Veterans Day, Monday, Nov. 11.

****************

COURTESY/ Wilson County News 2002